This summer I had the privilege of exploring Afghanistan on my bicycle, something which wouldn’t have been possible (or advisable) for the majority of the past 40 years when the country was plagued by wars. In this post I will share my experience, the route I took, and provide tips & information on the customs & logistics in Afghanistan.

The Route

I will be focussing on my crossing of the mountains, the Hindu Kush, in Central Afganistan, as I was likely the first person to cycle this route. Cycling on the highways, the Afghan ring road, which connects all major cities in the country is rather straightforward, and other travelers’ reports can be found on the web. I entered the country from Pakistan via the chaotic Torkham border. Afghanistan will require a visa for most nationalities, which will cost around $80 to $100. Due to the Taliban government not being recognized in all nations, this visa can be diffficult to obtain. Recommended embassies/consulates are in Peshawar PK (where I got mine), Termez UZ, Dubai UAE, or as a visa-onarrival at Shir Khan Bandar coming from Tajikistan.

Direction: It is advisable to cycle the route from East to West, as this will follow the flow of the Balkh river downstream, making the downhill ride easier. Don’t worry if you’re looking for a challenge, there will still be plenty of elevation gain regardless. The second reason is the handling of the permits: At this moment moment in time, every foreign traveler in Afghanistan is required to have a travel permit, often referred to as ‘Maktub’. You will need to obtain this paper in the provincial capital of every province you pass through. This could create major detours for cyclists. Luckily, in Kabul, the capital, it is possible to receive a single permit that is valid for all 34 provinces in the country. For this, you will need to head to the Ministry of Culture with your passport. The permit should be issued within a few minutes free of charge. The process in the provinicial capitals will be the same, although the Ministries might be difficult to find. Apparently it is also possible to pre-arrange all permits via tourist agencies, even if before you enter the country. If you decide to cycle West to East, this would probably be a worhwile investment.

Difficulty & Challenges:

On the map, the route doesn’t look too difficult, but it certainly wasn’t a ‘ride in the park’. The road will be unpaved from the town of Yakavalang until 20km after Kishindeh. It is often rough, but rarely impossible to cycle on. I would recommend tires with a width of at least 2 inches. There some minor stream crossings, potentially more challening ones in early summer (around May). Regardless of the direction you cycle, there will lots of short, but very steep climbs, at times when the locals had to build the road on the side of the mountain faces so it won’t get flooded by the river. You will likely have to push your bike in some of those bits. The great thing is that all of this result in little to no traffic.

Another challenge I had was the fierce headwind I faced basicially every single day going East to West. This might be seasonal, so do let me know your experience if you cycle this route.

Also challenging was the communication with the locals and authorities. Most people you will meet will be Hazara, an ethnic minority with Turkic and Mongol roots. They speak Dari, a Persian dialect. Most Talibs, even those stationed in the Hazara regions, will be ethnic Pashtuns, speaking Pashto. These two are not mutually intelligible, and not easy to learn, so I didn’t bother much and thought I could rely on Google Translate. In hindsight, this was a mistake, as probably two thirds of the people I met in the countryside were illiterate, rendering the translator useless. ‘Just use the speech translation feature’ you might think, unfortunatelly this requires an internet connection, which was non-existent most of the time. I was using an Afghan Wireless SIM card, which was recommend for the countryside, but connectivity was still very disappointing. Therefore I’d recommend either learning both languages to some extend, or make an audio recording of the translation output when you have internet, so you can play it when you don’t.

Logistics:

As mentioned before, make sure to get your travel permit. This will be checked along with your passport at the police (=Taliban) checkpoints, which are usually located just outside of cities, major intersections, or in sensitive areas. Checks are generally completed within two or three minutes, you will likely be asked about your plans, might be invited for a tea, or if you’re unlucky, be interrogated.

This happened to me one time in the town of Tarkhuj, but was likely caused by miscommunication between the different checkpoints. I was guided to the local security office, where the Talibs wanted to check phone and examinate my passport. They mainly checked my photos and WhatsApp messages, but remained respectful and eventually invited me for lunch and let me go, after they were convinced I wasn’t a spy or similiar.

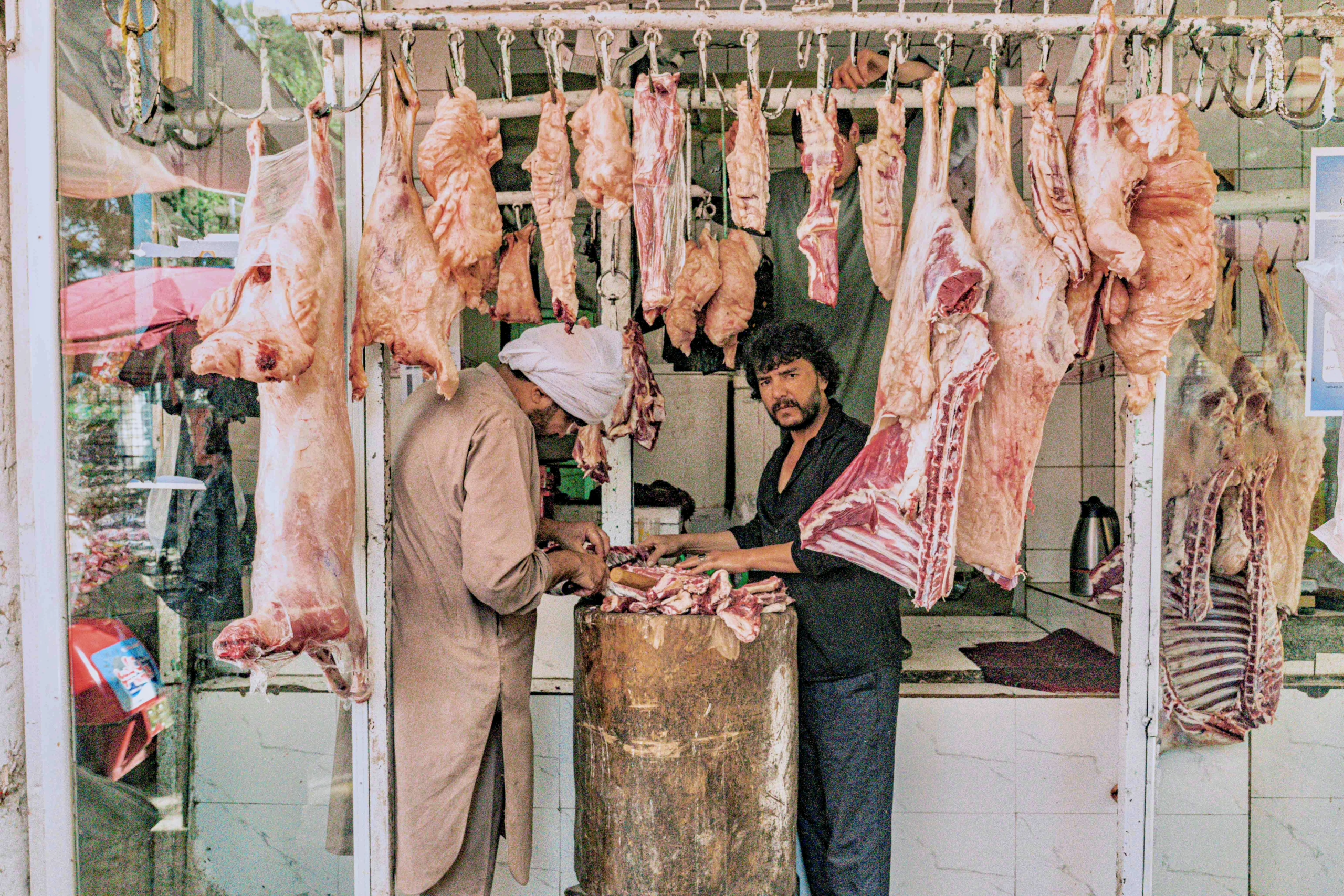

Regarding the food, in Kabul and other major cities you can find well-stocked supermarkets with Western products, in mid-sized cities like Bamyan you should also be able to find everything you need for a cycling trip, and local markets can be found in towns and bigger villages. Smaller villages might have a single small shop that sells some noodles or rice besides the usual junk food and energy drinks. You should come across at least one store per day, but I recommend carrying food for two days in case you break down in the middle of nowhere. Pharmacies are generally not found in villages.

While you can find some bike mechanics in Kabul or bigger cities, there won’t be any between Bamiyan and Mazar-e Sharif. So make sure you know how to fix your bike if needed. Even hitching a ride out of the mountains will be difficult, as most locals are using mules and donkeys as mode of transport.

Regarding restaurants, I’ve only come across two on the stretch between Yakavalang and Kishindeh. One in the town of Tarkhuj, which also doubles as a hotel (the only one between these two places), and another one near a coal mine at roughly 35.72700 66.98113. So you should bring a camping stove, and definitely a tent. I’d also recommend carrying a water filter, while bottled water will be available at most shops, this would require additional planning and might leave you in trouble in the owner of the single shop is out of town. Locals will be willing to help, but they will likely be drinking stream or well water, which your body might now be used to. You won’t die of thirst as you’re almost always next to the river and additional streams and springs can be found as well, but it’s advisable to filter/treat any water from natural sources.

Customs & Rules:

If you’re reading this article, you’re likely aware of the general situation in Afghanistan since the Taliban are back in power. So I’m just going to share my experience and practical information if you plan to travel to the country. First of all, women are allowed to visit Afghanistan independently, I’ve met two solo female travellers from the US and Australia in Kabul. Whether cycling alone as a woman is possible is yet to be determined, I don’t think anyone has tried it yet. I believe it should be possible, but going with a male partner would certainly make things easier, especially if you end up having problems, whether this might be an injury or trouble with the authorities. I’ve found that the older generation of Talibs are a lot more strict and conservative than the younger guys.

First, stuff you shouldn’t do:

- Photographing women & sensitive areas (checkpoints, military installations etc.)

- Striking up casual conversations with strangers of the opposite gender

- Wearing unappropiate clothes (no shorts for men, no tight clothes, long clothes & head scarf for women)

- Tell the Taliban how to think or run their country

Things that should be fine:

- Cyclist apparel (Men should be fine with tight/short lycra cycling clothes if you make the appearance of a ‘sports’ cyclist, combined with a helmet, cycling glasses etc. Probably not advised for women)

- Listening to music with headphones

- Asking the opposite gender for help, directions etc.

Note that the customs can vary starkly by the different regions. Pashtun regions tend to be stricter/more conservative, where pretty much all women will be wearing the Burka. In the Hazara regions, in which you will spend most time in (with this route), are more relaxed, and you will see barely any fully covered women, there are still schools open for them, and having ‘normal’ interactions with them should be possible.

Safety:

The scariest moment of this trip was when a thunderstorm was battering my exposed tent on the cliff overlooking the lake Band-e Amir at 3000m a.s.l..

The whole trip ended up being a lot more relaxed than I anticipated. While the Taliban remain designated as a terror organisation by the US, there is no need to worry about them if you stick to their rules. As the governing force, they are responsible for the safety in the country. Jihadist groups like ISIS-K haven’t been completely eradicated from Afghanistan, but the odds of being caught in an attack are minimal.

The fact that the Taliban is trying to encourage tourism, makes you want to believe that they are confident in having the country under control. This encouragement also means that there is no risk of ending up as a political prisoner, like it’s a possibility in Iran or Russia if you’re traveling on a Western passport.

As this route passes through the Hazara regions, I recommend reading up on the history and the relation between the Hazaras and the other ethnic groups in the country. Hazara embrace Shia-Islam, while the preodominantely Pashtun Taliban are Sunni-Muslims. Their differences have resulted in violent clashes in the past, and tensions remain, although it seemed fine when I was passing through the region.

Additionally, there is always the risk of natural disasters or other types of injuries. Recently an earthquake has claimed the lives of thousands near Jalalabad, a place I also passed through. There is a risk of flash floods, rockfall and landslides in the mountains, especially after heavy rainfall. Emergency services are lacking, organised rescues from remote places potentially impossible.

Lastly, Afghans are not renowned for safe driving. They are often speeding and not always paying attention. I experienced this first hand on my last day, when I was hit by a car going probably 40 miles while overtaking me. Miracuosely I walked away with some minor bruises and the bike also survived.

So, before going, stay in the loop with the latest news and conclude your own due diligence and travel at your own risk.

With that being said, despites its challenges, both physicially and mental, Afghanistan has been one of the most rewarding places I have visited. The locals are welcoming foreigners with open arms, regardless of their nationality. The Taliban were much less scary to deal with than expected. The food was delicious. And the landscapes were amongst the most stunning I have ever seen.

Would I visit it again one day? Probably. Would it have even more potential if some of the government’s policies were changed? Certainly.